Fernando Pessoa

| Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa | |

|---|---|

Fernando Pessoa photographed in 1914. |

|

| Born | June 13, 1888 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | November 30, 1935 (aged 47) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Occupation | Poet, writer and translator |

| Language | Portuguese, English (bilingual) |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Notable award(s) |

|

|

Influences

Edgar Allan Poe, Henri-Frédéric Amiel, Charles Maurras, Marinetti, Walt Whitman, Antero de Quental, António Nobre and Cesário Verde

|

|

|

Influenced

Almada Negreiros, Giannina Braschi, José Saramago, Mário Cesariny, Mário de Sá Carneiro, Gao Xingjian, Antonio Tabucchi

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature | |

Fernando António Nogueira de Seabra Pessoa, known mainly as Fernando Pessoa (Portuguese pronunciation: [fɨɾˈnɐ̃du pɨˈsoɐ]; b. June 13, 1888 in Lisbon, Portugal — d. November 30, 1935 in the same city at the Hospital of São Luís), was a Portuguese poet, writer, literary critic and translator, and one of the most significant literary figures of the 20th century. The critic Harold Bloom has referred to him in the book The Western Canon as the most representative poet of the 20th century, along with Pablo Neruda. He was trilingual in Portuguese, English, and in French.

Contents |

Early years in Durban

On 13 July 1893, when Pessoa was five, his father, Joaquim de Seabra Pessoa, died of tuberculosis. The following year, on 2 January, his younger brother Jorge, aged only one, also died. His mother Maria Madalena Pinheiro Nogueira married again in December 1895. In the beginning of 1896, he moved with his mother to Durban, capital of the former British Colony of Natal, where his stepfather João Miguel dos Santos Rosa, a military officer, had been appointed Portuguese consul. The young Pessoa received his early education at St. Joseph Convent School, a Catholic school run by Irish and French nuns. He moved to Durban High School in April, 1899, becoming fluent in English and developing an appreciation for English literature. During the "Matriculation Examination," for admission to the University of Cape Town, in November 1903, he was awarded the recently-created "Queen Victoria Memorial Prize" for best paper in English. While preparing to enter university, he also attended the Durban Commercial School, during one year, in the evening shift. Meanwhile he started writing short stories in English, some under the name of David Merrick, many of which he left unfinished [1].

At the age of sixteen, The Natal Mercury (July 9, 1904 edition) published his poem "Hillier did first usurp the realms of rhyme...", under the name of Charles Robert Anon, along with a small introductory text: "I read with great amusement...". In December, The Durban High School Magazine published his essay Macaulay [2]. From February to June, 1905, in the section "The Man in the Moon," The Natal Mercury also published at least four sonnets by Fernando Pessoa: "Joseph Chamberlain", "To England I", "To England II" and "Liberty" [3]. His poems often carried humorous versions of Anon as the author's name.

Ten years after his arrival, he sailed for Lisbon via the Suez Canal on board the "Herzog", leaving Durban for good at the age of seventeen. This journey inspired the poems "Opiário" (dedicated to his friend, the poet and writer Mário de Sá-Carneiro) published in March, 1915, in Orpheu nr.1 [4] and "Ode Marítima" (dedicated to the futurist painter Santa Rita Pintor) published in June, 1915, in Orpheu nr.2 [5] by his heteronym Álvaro de Campos.

Adult life in Lisbon

|

| Fernando Pessoa, from «Lisbon Revisited» (1926), ed. and tr. Edwin Honig and Susan M. Brown. |

While his family remained in South Africa, Pessoa returned to Lisbon in 1905, to study diplomacy. After a period of illness, and two years of poor results, a student strike put an end to his studies and in August, 1907, he started working at R.G. Dun & Company, an American mercantile informations agency (currently D&B - Dun & Bradstreet). His grandmother died in September and left him a small inheritance that he spent on setting up his own publishing house, the Empreza Ibis. The venture was not a success and closed down in 1910. The Ibis, a sacred bird in the Ancient Egypt would remain an important symbolic reference for him.

Upon his return to Lisbon, Pessoa began to complement his British education with Portuguese culture, as an autodidact. The Republican Revolution of 1910 and associated patriotic atmosphere was certainly of major importance in the formation of the writer. His stepuncle Henrique dos Santos Rosa, a retired general and poet, introduced the young Pessoa to Portuguese poetry, notably the Romantics and Symbolists of 19th century [6].

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa entered the literary world with a critic, published in the cultural journal A Águia, that triggered one of the most important literary debates in the Portuguese intellectual world of the 20th century: the polemic super-Camões. In 1915 a group of artists and poets, including Fernando Pessoa, Almada Negreiros and Mário de Sá-Carneiro, created the literary magazine Orpheu [7], which introduced modernist literature to Portugal. Only two issues were published (Jan-Feb-Mar and Apr-May-Jun, 1915), the third failed due to funding difficulties. The third issue of Orpheu was lost during many years and it was finally recovered and published in 1984 [8].

Pessoa also founded the literary review Athena (1924–1925), which published the heteronym Ricardo Reis. Along with his activity of free-lance commercial translator, Fernando Pessoa had an intense activity as a writer and literary critic, contributing to journals and magazines such as A Águia (1912–1913), A Renascença (1914), Orpheu (1915), Exílio (1916), Portugal Futurista (1917), Contemporânea (1922–1923), Presença (1927–1934) and Sudoeste (1935). He also published as a political analyst and literary critic in magazines and newspapers such as Teatro (1913), O Jornal (1915), Acção (1919–1920), Diário de Lisboa (1924–1935), Revista de Comércio e Contabilidade (1926) and Fama (1932–1933).

Pessoa the flâneur

If Franz Kafka is the writer of Prague, Fernando Pessoa is certainly the writer of Lisbon. After his return to Portugal, when he was seventeen, Pessoa barely left his beloved city, which inspired the poems "Lisbon Revisited" (1923 and 1926), by his heteronym Álvaro de Campos. From 1905 to 1921, when his family returned from Pretoria after the death of his stepfather, he lived in fifteen different places around the city[9], moving from a rented room to another according to his financial troubles and the troubles of the young Portuguese Republic.

Pessoa had the flâneur's regard, namely through the eyes of Bernardo Soares, another of his heteronyms [10]. This character was supposedly an accountant, working at an office in Douradores Street, where Vasques was the boss, and living in the same downtown street, a world that Pessoa knew quite well due to his long career as free lance correspondence translator. In fact, from 1907 until his death, in 1935, Pessoa worked in twenty one firms located in Lisbon's downtown, sometimes in two or three of them simultaneously [11]. In The Book of Disquiet, Bernardo Soares describes some of those typical places and its "atmosphere".

Pessoa was a frequent customer at Martinho da Arcada, a centennial coffee house downtown, almost an "office" for his private business and literary concerns, where he used to meet friends in the 1920's. He also frequented other coffee shops, bars and restaurants, a number of which no longer exist. The statue of Fernando Pessoa (above) can be seen outside A Brasileira, one of the prefered places of the young writers and artists of the group of orpheu during the 1910's. This coffee shop, in the aristocratic district of Chiado, is quite close to Pessoa's birthplace: 4, Largo de São Carlos (in front of the Opera House) [12], one of the most elegant neighborhoods of Lisbon [13]. In 1925, Pessoa wrote in English a guidebook to Lisbon but it remained unpublished until 1992 [14].

Writing a lifetime

In his early years, Pessoa was influenced by major English classic poets such as Shakespeare, Milton or Spenser and romantics like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats. Later, he was also influenced by French symbolists Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé, mainly by Portuguese poets as Antero de Quental, Gomes Leal, Camilo Pessanha, Cesário Verde, António Nobre or Teixeira de Pascoaes, and modernists as Yeats, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, among many other writers [1].

During World War I, Pessoa wrote to a number of British publishers in order to print his collection of English verse The Mad Fiddler (unpublished during his lifetime), but it was refused. However, in 1920, the prestigious literary review Athenaeum included one of those poems [15]. Since the British publication failed, in 1918 Pessoa published in Lisbon two slim volumes of English verse: Antinous [16] and 35 Sonnets [17], received by the British literary press without enthusiasm [18]. Along with two associates, he founded another publishing house, Olisipo, which published in 1921 a further two English poetry volumes: English Poems I-II and English Poems III by Fernando Pessoa.

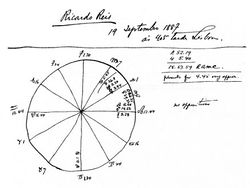

Pessoa translated into English some Portuguese books and from English the poems "The Raven", "Annabel Lee" and "Ulalume"[19] by Edgar Allan Poe which, along with Walt Whitman, strongly influenced him. He also translated into Portuguese a number of esoteric books by leading Theosophists such as C. W. Leadbeater and Annie Besant [20]. Pessoa was influenced by occultism and developed an interest on spiritism and astrology. He was an amateur astrologue, elaborating astral charts for friends and even for himself and the heteronyms. His interest in occultism led Pessoa to correspond with Aleister Crowley. Later he helped Crowley plan an elaborate fake suicide when he visited Portugal in 1930 [21]. Pessoa translated Crowley's poem "Hymn To Pan" into Portuguese, and the catalogue of Pessoa's library shows that he possessed copies of Crowley's Magick in Theory and Practice and Confessions. Pessoa also wrote on Crowley's doctrine of Thelema in several fragments, including Moral [22].

Pessoa died of cirrhosis in 1935, at the age of forty-seven, almost unknown to the public and with only one book published in Portuguese: "Mensagem" (Message). He left a lifetime of unpublished and unfinished work (over 25,000 pages manuscript and typed that have been housed in the Portuguese National Library since 1988). The heavy burden of editing this huge work is still in progress. In 1988 (the centenary of his birth), Pessoa's remains were moved to the Hieronymites Monastery, in Lisbon, where Vasco da Gama, Luís de Camões, and Alexandre Herculano are also buried. Pessoa's portrait was on the 100-escudo banknote.

Heteronyms

Pessoa's earliest heteronym, at the age of six, was the Chevalier de Pas. Other childhood heteronyms included Dr. Pancrácio and David Merrick, followed by Charles Robert Anon and Alexander Search, succeeded by others. Translator Richard Zenith notes that Pessoa eventually established at least seventy-two heteronyms [23]. According to Pessoa himself, there were three main heteronyms: Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos and Ricardo Reis. The heteronyms possess distinct biographies, temperaments, philosophies, appearances and writing styles [24].

Fernando Pessoa on the heteronyms

«How do I write in the name of these three? Caeiro, through sheer and unexpected inspiration, without knowing or even suspecting that I’m going to write in his name. Ricardo Reis, after an abstract meditation, which suddenly takes concrete shape in an ode. Campos, when I feel a sudden impulse to write and don’t know what. (My semi-heteronym Bernardo Soares, who in many ways resembles Álvaro de Campos, always appears when I'm sleepy or drowsy, so that my qualities of inhibition and rational thought are suspended; his prose is an endless reverie. He’s a semi-heteronym because his personality, although not my own, doesn’t differ from my own but is a mere mutilation of it. He’s me without my rationalism and emotions. His prose is the same as mine, except for certain formal restraint that reason imposes on my own writing, and his Portuguese is exactly the same – whereas Caeiro writes bad Portuguese, Campos writes it reasonably well but with mistakes such as "me myself" instead of "I myself", etc.., and Reis writes better than I, but with a purism I find excessive...)»[25].

George Steiner on Fernando Pessoa: «A man of many parts»

«Pseudonymous writing is not rare in literature or philosophy (Kierkegaard provides a celebrated instance). 'Heteronyms', as Pessoa called and defined them, are something different and exceedingly strange. For each of his 'voices', Pessoa conceived a highly distinctive poetic idiom and technique, a complex biography, a context of literary influence and polemics and, most arrestingly of all, subtle interrelations and reciprocities of awareness. Octavio Paz defines Caeiro as 'everything that Pessoa is not and more'.

He is a man magnificently at home in nature, a virtuoso of pre-Christian innocence, almost a Portuguese teacher of Zen. Reis is a stoic Horatian, a pagan believer in fate, a player with classical myths less original than Caeiro, but more representative of modern symbolism. De Campos emerges as a Whitmanesque futurist, a dreamer in drunkenness, the Dionysian singer of what is oceanic and windswept in Lisbon. None of this triad resembles the metaphysical solitude, the sense of being an occultist medium which characterise Pessoa's 'own' intimate verse.» [26]

List of Known Heteronyms

| No. | Name | Type | *Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fernando Antonio Nogueira Pessoa | himself | Commercial correspondent in Lisbon |

| 2 | Fernando Pessoa | orthonym | Poet and prose writer |

| 3 | Fernando Pessoa | autonym | Poet and prose writer |

| 4 | Fernando Pessoa | heteronym | Poet, a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 5 | Alberto Caeiro | heteronym | Poet, author of 'O guardador de Rebanhos','O Pastor Amoroso' and 'Poemos inconjuntos', master of Fernando Pessoa heteronyms, Alvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, Antonio Mora and Coelho Pacheco |

| 6 | Ricardo Reis | heteronym | Poet and prose writer, author of 'Odes' and texts on the work of Alberto Caeiro |

| 7 | Federico Reis | heteronym/para-heteronym | Essayist, brother of Ricardo Reis, upon whom he writes |

| 8 | Álvaro de Campos | heteronym | Poet and prose writer, a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 9 | Antonio Mora | heteronym | Philosopher and sociologist, theorist of Neopaganism, a pupil of Alberto Caeiro |

| 10 | Claude Pasteur | heteronym/semi-heteronym | French, translator of "CADERNOS DE RECONSTRUÇÃO PAGÃ" conducted by Antonio Mora |

| 11 | Bernardo Soares | heteronym/semi-heteronym | Poet and prose writer, author of the 'Book of Disquiet' |

| 12 | Vicente Guedes | heteronym/semi-heteronym | Translator, poet, and director of Ibis Press, author of a paper |

| 13 | Gervasio Guedes | heteronym/para-heteronym | Author of the text 'A Coroação of Jorge Quinto' |

| 14 | Alexander Search | heteronym | Poet and short story writer |

| 15 | Charles James Search | heteronym/para-heteronym | Translator and essayist, brother of Alexander Search |

| 16 | Jean-Méluret of Seoul | heteronym/proto-heteronym | French Poet and Essayist |

| 17 | Rafael Baldaya | heteronym | Astrologer and author of 'Tratado da Negação' and 'Princípios de Metaphysica Esotérica' |

| 18 | Barão de Teivo | heteronym | Prose writer, author of "Educação do Stoica" and "Daphnis e Chloe" |

| 19 | Charles Robert Anon | heteronym/semi-heteronym | Poet, philosopher and story writer |

| 20 | A. A. Crosse | pseudonym/proto-heteronym | Author and Puzzle-solver |

| 21 | Thomas Crosse | heteronym/proto-heteronym | English epic character/occultist, popularised in Portuguese culture |

| 22 | I. I. Crosse | heteronym/para-heteronym | ---- |

| 23 | David Merrick | heteronym/semi-heteronym | Poet, storyteller and Playwright |

| 24 | Lucas Merrick | heteronym/para-heteronym | Short story writer, perhaps brother David Merrick |

| 25 | Pêro Botelho | heteronym/pseudonym | Short story writer and author of Letters |

| 26 | Abilio Quaresma | heteronym/character/meta-heteronym | A character inspired by Botelho Pêro and author of short detective stories |

| 27 | Inspector Guedes | character/meta-heteronym? | A character inspired by Botelho Pêro and author of short detective stories |

| 28 | Uncle Pork | pseudonym/character | A character inspired by Botelho Pêro and author of short detective stories |

| 29 | Frederick Wyatt | alias/heteronym | Poet and prose writer (in the english language) |

| 30 | Rev. Walter Wyatt | character | Possibly brother of Frederick Wyatt |

| 31 | Alfred Wyatt | character | Another brother of Frederick Wyatt/a resident of Paris |

| 32 | Maria José | heteronym/proto-heteronym | Wrote and signed «A Carta da Corcunda para o Serralheiro» |

| 33 | Chevalier de Pas | pseudonym/proto-heteronym | Author of poems and letters |

| 34 | Efbeedee Pasha | heteronym/proto-heteronym | Author of humoristic "Stories" |

| 35 | Faustino Antunes/A. Moreira | heteronym/pseudonym | Psychologist, author of "Ensaio sobre a Intuição» |

| 36 | Carlos Otto | heteronym/proto-heteronym | Poet and author of "Tratado de Lucta Livre" |

| 37 | Michael Otto | pseudonym/para-heteronym | Probably brother of Carlos Otto who was entrusted with the translation into English of "Tratado de Lucta Livre" |

| 38 | Sebastian Knight | proto-heteronym/alias | |

| 39 | Horace James Faber | heteronym/semi-heteronym | short story writer and essayist (in English) |

| 40 | Navas | heteronym/para-heteronym | Translated Horace James Faber in Portuguese |

| 41 | Pantaleão | heteronym/proto-heteronym | Poet and prose |

| 42 | Torquato Fonseca Mendes da Cunha Rey | heteronym/meta-heteronym | Deceased author of a text, Pantaleão decided to publish |

| 43 | Joaquim Moura Costa | proto-heteronym/semi-heteronym | satirical poet, Republican activist, member of "O PHOSPHORO" |

| 44 | Sher Henay | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Compiler and author of the preface of a sensationalist anthology in English |

| 45 | Anthony Gomes | semi-heteronym/character | Philosopher, author of "Historia Cómica do Affonso Çapateiro" |

| 46 | Professor Trochee | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Author of an essay with humorous advice for young poets |

| 47 | Willyam Links Esk | character | Signed a letter written in English on 13/4/1905 |

| 48 | António de Seabra | pseudonym/proto-heteronym | Literary critic |

| 49 | João Craveiro | pseudonym/proto-heteronym | Journalist, follower of Sidonio Pereira |

| 50 | Tagus | pseudonym | Collaborator in "NATAL MERCURY" (Durban, South Africa) |

| 51 | Pipa Gomes | draft heteronym | Collaborator in "O PHOSPHORO" |

| 52 | Ibis | character/a pseudonym | A character from Pessoa's childhood, accompanying him until the end of his life/also signed poems |

| 53 | Dr. Gaudencio Turnips | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Director of "O PALRADOR", English-Portuguese journalist and humorist |

| 54 | Pip | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Poet, humorous anecdotes. Predecessor of Dr. Pancrazio |

| 55 | Dr. Pancrazio | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Storyteller, poet and creator of charades |

| 56 | Luís António Congo | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Collaborator in "O PALRADOR", columnist and presenter of Lanca Eduardo |

| 57 | Eduardo Lance | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Luso-Brazilian poet |

| 58 | A. Francisco de Paula Angard | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Collaborator in "O PALRADOR", author of «textos scientificos» |

| 59 | Pedro da Silva Salles/Zé Pad | proto-heteronym/alias | Author and director of the section of anecdotes at "O PALRADOR" |

| 60 | José Rodrigues do Valle/Scicio | proto-heteronym/alias | "O PALRADOR", author of charades and 'literary manager' |

| 61 | Dr. Caloiro | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", reporter and author of «A pesca das pérolas» |

| 62 | Adolph Moscow | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", novelist, author of «Os Rapazes de Barrowby» |

| 63 | Marvell Kisch | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in "O PALRADOR", called «A Riqueza de um Doido» |

| 64 | Gabriel Keene | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in "O PALRADOR", called «Em Dias de Perigo» |

| 65 | Sableton-Kay | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | Author of a novel announced in "O PALRADOR", called «A Lucta Aerea» |

| 66 | Morris & Theodor | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 67 | Diabo Azul | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 68 | Parry | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 69 | Gallião Pequeno | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 70 | Urban Accursio | alias | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 71 | Cecília | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 72 | José rasteiro | proto-heteronym/pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of proverbs and riddles |

| 73 | Nympha Negra | pseudonym | "O PALRADOR", author of charades |

| 74 | Diniz da Silva | pseudonym/proto-heteronym | Author of the poem "Loucura" and collaborator in "EUROPE" |

| 75 | Herr Prosit | pseudonym | Translator of 'O Estudante de Salamanca' by Espronceda |

| 76 | Henry More | proto-heteronym | Author and prose writer |

| 77 | Wardour | character? | Poet |

| 78 | J. M. Hyslop | character? | Poet |

| 79 | Vadooisf ? | Character? | Poet |

Alberto Caeiro

|

| Alberto Caeiro: "The Keeper of Herds" (O Guardador de Rebanhos) (tr. Richard Zenith) |

Alberto Caeiro was Pessoa's first great heteronym; summarized by Pessoa, writing: He sees things with the eyes only, not with the mind. He does not let any thoughts arise when he looks at a flower... the only thing a stone tells him is that it has nothing at all to tell him... this way of looking at a stone may be described as the totally unpoetic way of looking at it. The stupendous fact about Caeiro is that out of this sentiment, or rather, absence of sentiment, he makes poetry.

What this means, and what makes Caeiro such an original poet is the way he apprehends existence. He does not question anything whatsoever; he calmly accepts the world as it is. The recurrent themes to be found in nearly all of Caeiro's poems are wide-eyed child-like wonder at the infinite variety of nature, as noted by a critic. He is free of metaphysical entanglements. Central to his world-view is the idea that in the world around us, all is surface: things are precisely what they seem, there is no hidden meaning anywhere.

He manages thus to free himself from the anxieties that batter his peers; for Caeiro, things simply exist and we have no right to credit them with more than that. Our unhappiness, he tells us, springs from our unwillingness to limit our horizons. As such, Caeiro attains happiness by not questioning, and by thus avoiding doubts and uncertainties. He apprehends reality solely through his eyes, through his senses. What he teaches us is that if we want to be happy we ought to do the same. Octavio Paz called him the innocent poet. Paz made a shrewd remark on the heteronyms: In each are particles of negation or unreality. Reis believes in form, Campos in sensation, Pessoa in symbols. Caeiro doesn't believe in anything. He exists.[27]

Poetry before Caeiro was essentially interpretative; what poets did was to offer an interpretation of their perceived surroundings; Caeiro does not do this. Instead, he attempts to communicate his senses, and his feelings, without any interpretation whatsoever.

Caeiro attempts to approach Nature from a qualitatively different mode of apprehension; that of simply perceiving (an approach akin to phenomenological approaches to philosophy). Poets before him would make use of intricate metaphors to describe what was before them; not so Caeiro: his self-appointed task is to bring these objects to the reader's attention, as directly and simply as possible. Caeiro sought a direct experience of the objects before him.

As such it is not surprising to find that Caeiro has been called an anti-intellectual, anti-Romantic, anti-subjectivist, anti-metaphysical...an anti-poet, by critics; Caeiro simply—is. He is in this sense very unlike his creator Fernando Pessoa: Pessoa was besieged by metaphysical uncertainties; these were, to a large extent, the cause of his unhappiness; not so Caeiro: his attitude is anti-metaphysical; he avoided uncertainties by adamantly clinging to a certainty: his belief that there is no meaning behind things. Things, for him, simply—are.

Caeiro represents a primal vision of reality, of things. He is the pagan incarnate. Indeed Caeiro was not simply a pagan but paganism itself.[28]

The critic Jane M. Sheets sees the insurgence of Caeiro—who was Pessoa's first major heteronym—as essential in founding the later poetic personas: By means of this artless yet affirmative anti-poet, Caeiro, a short-lived but vital member of his coterie, Pessoa acquired the base of an experienced and universal poetic vision. After Caeiro's tenets had been established, the avowedly poetic voices of Campos, Reis and Pessoa himself spoke with greater assurance.[29]

Ricardo Reis

|

| Ricardo Reis |

Reis sums up his philosophy of life in his own words, admonishing: 'See life from a distance. Never question it. There's nothing it can tell you.' Like Caeiro, whom he admires, Reis defers from questioning life. He is a modern pagan who urges one to seize the day and accept fate with tranquility. 'Wise is the one who does not seek', he says; and continues: 'the seeker will find in all things the abyss, and doubt in himself.' In this sense Reis shares essential affinities with Caeiro.

Believing in the Greek gods, yet living in a Christian Europe, Reis feels that his spiritual life is limited, and true happiness cannot be attained. This, added to his belief in Fate as a driving force for all that exists, as such disregarding freedom, leads to his epicureanist philosophy, which entails the avoidance of pain, defending that man should seek tranquility and calm above all else, avoiding emotional extremes.

Where Caeiro wrote freely and spontaneously, with joviality, of his basic, meaningless connection to the world, Reis writes in an austere, cerebral manner, with premeditated rhythm and structure and a particular attention to the correct use of the language, when approaching his subjects of, as characterized by Richard Zenith,'the brevity of life, the vanity of wealth and struggle, the joy of simple pleasures, patience in time of trouble, and avoidance of extremes'.

In his detached, intellectual approach, he is closer to Fernando Pessoa's constant rationalization, as such representing the ortonym's wish for measure and sobriety and a world free of troubles and respite, in stark contrast to Caeiro's spirit and style. As such, where Caeiro's predominant attitude is that of joviality, his sadness being accepted as natural ('My sadness,' Caeiro says, 'is a comfort for it is natural and right.'), Reis is marked by melancholy, saddened by the impermanence of all things.

Ricardo Reis is the main character of José Saramago's 1986 novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis.

Álvaro de Campos

|

| Álvaro de Campos: "The Tobacco Shop" (Tabacaria) (tr. Miguel Peres dos Santos) |

Álvaro de Campos manifests, in a way, as an hyperbolic version of Pessoa himself. Of the three heteronyms he is the one who feels most strongly, his motto being 'to feel everything in every way.' 'The best way to travel,' he wrote, 'is to feel.' As such, his poetry is the most emotionally intense and varied, constantly juggling two fundamental impulses: on the one hand a feverish desire to be and feel everything and everyone, declaring that 'in every corner of my soul stands an altar to a different god '(alluding to Walt Whitman's desire to 'contain multitudes'), on the other, a wish for a state of isolation and a sense of nothingness.

As a result, his mood and principles varied between violent, dynamic exultation, as he fervently wishes to experience the entirety of the universe in himself, in all manners possible (a particularly distinctive trait in this state being his futuristic leanings, including the expression of great enthusiasm as to the meaning of city life and its components) and a state of nostalgic melancholy, where life is viewed as, essentially, empty.

One of the poet's constant preoccupations, as part of his dichotomous character, is that of identity: he does not know who he is, or rather, fails at achieving an ideal identity. Wanting to be everything, and inevitably failing, he despairs. Unlike Caeiro, who asks nothing of life, he asks too much. In his poetic meditation 'Tobacco Shop' he asks:

- How should I know what I'll be, I who don't know what I am?

- Be what I think? But I think of being so many things!

Fernando Pessoa-himself

|

| Fernando Pessoa-himself: "Autopsychography" (Autopsicografia) (tr. Richard Zenith) |

'Fernando Pessoa-himself' is not the 'real' Fernando Pessoa. Like Caeiro, Reis and Campos—Pessoa 'himself' embodies only aspects of the poet, Fernando Pessoa's personality is not stamped in any given voice; his personality is diffused through the heteronyms. For this reason 'Fernando Pessoa-himself' stands apart from the poet proper.

'Pessoa' shares many essential affinities with his peers, Caeiro and Campos in particular. Lines crop up in his poems that may as well be ascribed to Campos or Caeiro. It is useful to keep this in mind as we read this exposition.

The critic Leland Guyer sums up 'Pessoa': "the poetry of the orthonymic Fernando Pessoa normally possesses a measured, regular form and appreciation of the musicality of verse. It takes on intellectual issues, and it is marked by concern with dreams, the imagination and mystery."

Richard Zenith calls 'Pessoa' '[Pessoa's] most intellectual and analytic poetic persona.' Like Álvaro de Campos, Pessoa-himself was afflicted with an acute identity crisis. Pessoa-himself has been described as indecisive and doubt plagued, as restless. Like Campos he can be melancholic, weary, resigned. The strength of Pessoa-himself's poetry rests in his ability to suggest a sense of loss; of sorrow for what can never be.

A constant theme in Pessoa's poetry is Tédio, or Tedium. The dictionary defines this word simply as 'a condition of being tedious; tediousness or boredom.' This definition does not sufficiently encompass the peculiar brand of tedium experienced by Pessoa-himself. His is more than simple boredom: it is from a world of weariness and disgust with life; a sense of the finality of failure; of the impossibility of having anything to want.

'The impossibility of having anything to want': this is Tédio for Pessoa-himself. It is one thing to have nothing to do or want, but to be deprived even of this...is tedium. Kierkegaard tells how if asked to choose between the two; between a perpetual state of boredom, or eternal bodily pain; he would choose—eternal bodily pain. Pessoa-himself, it would seem, would concur with the melancholy Dane.

Summaries of selected works

Message

Mensagem in Portuguese, (from the Latin "MENS AGitat molEM", which means, "The Mind moves/commands the Matter) is a very unusual twentieth century book: it is a symbolist epic made up of 44 short poems organized in three parts or Cycles [30]:

The first, called "Brasão" (Coat-of-Arms), relates Portuguese historical protagonists to each of the fields and charges in the Portuguese coat-of-arms. The first two poems ("The castles" and "The escutcheons") draw inspiration from the material and spiritual natures of Portugal. Each of the remaining poems associates to each charge a historical personality. Ultimately they all lead to the Golden Age of Discovery.

The second Part, called "Mar Português" (Portuguese Sea), references the country's Age of Portuguese Exploration and to its seaborne Empire that ended with the death of King Sebastian at Ksar-el-Kebir (in 1578). Pessoa brings the reader to the present as if he had woken up from a dream of the past, to fall in a dream of the future: he sees King Sebastian returning and still bent on accomplishing a Universal Empire, like King Arthur heading for Avalon...

The third Cycle, called "O Encoberto" ("The Hidden One"), is the most disturbing. It refers to Pessoa's vision of a future world of peace and the Fifth Empire. After the Age of Force, (Vis), and Taedium (Otium) will come Science (understanding) through a reawakening of "The Hidden One", or "King Sebastian". The Hidden One represents the fulfillment of the destiny of mankind, designed by God since before Time, and the accomplishment of Portugal.

One of the most famous quotes from Mensagem is the first line from O Infante (belonging to the second Part), which is Deus quer, o homem sonha, a obra nasce (which translates roughly to "God wills it, man dreams it, it is born"). That means 'Only by God's will man does', a full comprehension of man's subjection to God's wealth. Another well-known quote from Mensagem is the first line from Ulysses, "O mito é o nada que é tudo" (a possible translation is "The myth is the nothing that is all"). This poem refers Ulysses, king of Ithaca, as Lisbon's founder (recalling an ancient Greek myth) [31].

Literary essays

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa wrote a set of essays (later collected as The New Portuguese Poetry) for the cultural journal A Águia (The Eagle), founded in Oporto, in December 1910, and run by the republican association Renascença Portuguesa [32]. In the first years of the Portuguese Republic, this cultural association was started by republican intellectuals led by the writer and poet Teixeira de Pascoaes, philosopher Leonardo Coimbra and historian Jaime Cortesão, aiming for the renewal of Portuguese culture through the aesthetic movement called Saudosismo [33]. The first series of two articles engage the issue 'The new Portuguese poetry viewed sociologically' (nos. 4 and 5 ); the second series of three articles is entitled 'The psychological aspect of the new Portuguese poetry' (nos. 9,11 and 12). These writings were strongly encomiastic to saudosist literature, namely the poetry of Teixeira de Pascoaes and Mário Beirão. The articles disclose Pessoa as a connoisseur of modern European literature and an expert of recent literary trends. On the other hand, he does not care much for a methodology of analysis or problems in the history of ideas. He states his confidence that Portugal would soon produce a great poet - a super-Camões – pledged to make an important contribution for European culture, and indeed, for humanity [34].

Philosophical essays

The philosophical notes of young Fernando Pessoa, mostly written between 1905 and 1912, illustrate his debt to the history of Philosophy more through commentators than through a first-hand protracted reading of the Classics, ancient or modern. The issues he engages with pertain to every philosophical discipline and are dealt with a large profusion of concepts, creating a vast semantic spectrum in texts whose length oscillates between half a dozen lines and half a dozen pages and whose density of analysis is extremely variable; simple paraphrasis, expression of assumptions and original speculation.

Pessoa sorted the philosophical systems thus:

- Relative Spiritualism and relative Materialism privilege "Spirit" or "Matter" as the main pole that organizes data around Experience.

- Absolute Spiritualist and Absolute Materialist "deny all objective reality to one of the elements of Experience".

- The materialistic Pantheism of Spinoza and the spiritualizing Pantheism of Malebranche, "admit that experience is a double manifestation of any thing that in its essence has no matter neither spirit".

- Considering both elements as an illusory manifestation", of a transcendent and true and alone realities, there is Transcendentalism, inclined into matter with Schopenhauer, or into spirit, a position where Bergson could be emplaced.

- A terminal system "the limited and summit of metaphysics" would not radicalize - as poles of experience one of the singled categories - matter, relative, absolute, real, illusory, spirit. Instead, matching all categories, it takes contradiction as "the essence of the universe" and defends that "an affirmation is so more true insofar the more contradiction involves". The transcendent must be conceived beyond categories. There is one only and eternal example of it. It is that cathedral of thought -the philosophy of Hegel.

Such pantheist transcendentalism is used by Pessoa to define the project that "encompasses and exceeds all systems"; to characterize the new poetry of Saudosismo where the "typical contradiction of this system" occurs; to inquire what are the social and politic results of its adoption as the leading cultural paradigm; and, at last, he hints that metaphysics and religiosity strive "to find in everything a beyond".

List of works

Books by Fernando Pessoa

- Collected Poems of Álvaro de Campos, Vol. 2, 1928–1935, Translated from the Portuguese by Chris Daniels, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2009. ISBN 9781905700257 [3]

- Lisbon - What the Tourist Should See, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2008. ISBN 978190570752 [4]

- The Collected Poems of Alberto Caeiro, Translated from the Portuguese by Chris Daniels, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2007. ISBN 9781905700240 [5]

- Selected English Poems, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2007. ISBN 9781905700264 [6]

- Message, Translated from the Portuguese by Jonathan Griffin, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2007. ISBN 9781905700271 [7]

- Selected English Poems , ed. Tony Frazer, Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books, 2007. ISBN 1905700261

- A Centenary Pessoa, tr. Keith Bosley & L. C. Taylor, foreword by Octavio Paz, Carcanet Press, 2006. ISBN 1857547241

- A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin Classics, 2006. ISBN 0-14-303955-5

- The Education of the Stoic, tr. Richard Zenith, afterword by Antonio Tabucchi, Exact Change, 2004. ISBN 1878972405

- The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin classics, 2003. ISBN 9780141183046

- The Selected Prose of Fernando Pessoa, tr. Richard Zenith, Grove Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8021-3914-0

- Sheep's Vigil by a Fervent Person: A Translation of Alberto Caeiro, tr. Eirin Moure, House of Anansi, 2001. ISBN 0887846602

- Selected Poems: with New Supplement tr. Jonathan Griffin, Penguin Classics; 2nd edition, 2000. ISBN 0141184337

- Fernando Pessoa & Co: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Grove Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8021-3627-3

- Poems of Fernando Pessoa, anthology ed. & tr. Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown, City Lights Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-87286-342-5

- The Keeper of Sheep, bilingual edition, tr. Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown, Sheep Meadow, 1997. ISBN 1878818457

- Message, tr. Jonathan Griffin, introduction by Helder Macedo, Menard Press, 1992. ISBN 190570027X

- The Book of Disquietude, tr. Richard Zenith, Carcanet Press, 1991. ISBN 0-14-118304-7

- The Book of Disquiet, tr. Iain Watson, Quartet Books, 1991. ISBN 0704301539

- The Book of Disquiet, tr. Alfred Mac Adam, New York NY: Pantheon Books, 1991. ISBN 0679402349

- The Book of Disquiet, tr. Margaret Jull Costa, London, New York NY: Serpent's Tail, 1991, ISBN 1852422041

- Fernando Pessoa: Self-Analysis and Thirty Other Poems, tr. George Monteiro, Gavea-Brown Publications, 1989. ISBN 0943722144

- Always Astonished, tr. Edwin Honig, San Francisco CA: City Lights, 1988. ISBN 9780872862289

- Selected Poems by Fernando Pessoa, tr. Edwin Honig, Swallow Press, 1971. ISBN B000XU4FE4

- ENGLISH POEMS by Fernando Pessoa, 2 vol. ( vol. 1 part I - Antinous, part II - Inscriptions; vol. 2 part III - Epithalamium), Lisbon: Olisipo, 1921 (vol. 1 - 20 p., vol. 2 - 16 p., 24 cm). http://purl.pt/13967

- 35 SONNETS by Fernando Pessoa, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918 (20 p., 20 cm). http://purl.pt/13963

- ANTINOUS: a poem by Fernando Pessoa, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918 (16 p., 20 cm). http://purl.pt/13961

See also

- The Book Of Disquiet

- Orpheu

- heteronym

- Portuguese Poetry

- Universidade Fernando Pessoa

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ZENITH, Richard (2008), Fotobiografias Século XX: Fernando Pessoa, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores.

- ↑ MONTEIRO, Maria da Encarnação (1961), Incidências Inglesas na Poesia de Fernando Pessoa, Coimbra: author ed.

- ↑ JENNINGS, H.D. (1984), Os Dois Exilios, Porto: Centro de Estudos Pessoanos

- ↑ http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/23620 Orpheu nr.1

- ↑ http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/23621 Orpheu nr.2

- ↑ ZENITH, Richard (2008), Fotobiografias do Século XX: Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, p. 78.

- ↑ Orpheu Nr. 1, Jan-Feb-Mar 1915 at the Portuguese National Library.

- ↑ ORPHEU 3, preparação do texto, introdução e cronologia de Arnaldo Saraiva. Lisboa: Edições Ática.

- ↑ ZENITH, Richard (2008), Fotobiografias do Século XX: Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, pp. 194-195.

- ↑ GUERREIRO, Ricardina (2004), De Luto por Existir: a melancolia de Bernardo Soares à luz de Walter Benjamin. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim, p. 159.

- ↑ SOUSA, João Rui de (2010), Fernando Pessoa Empregado de Escritório, 2nd ed. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim.

- ↑ Teatro Nacional de São Carlos Lisbon's Opera House.

- ↑ DIAS, Marina Tavares (2002), Lisboa nos Passos de Pessoa: uma cidade revisitada através da vida e da obra do poeta / Lisbon in Pessoa's footsteps: a Lisbon tour through the life and poetry of Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Quimera

- ↑ PESSOA, Fernando (1992). Lisboa: o que o turista deve ver, Portuguese / English edition. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, 3rd. edition 2006.

PESSOA, Fernando (2008). Lisbon: what the tourist should see. Exeter (UK): Shearsman Books. - ↑ TERLINDEN, Anne (1990). Fernando Pessoa: the bilingual portuguese poet A Critical Study of «The Mad Fidler». Bruxels: Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis>[1].

- ↑ Antinous at the Portuguese National Library.

- ↑ 35 Sonnets at the Portuguese National Library.

- ↑ The Times Literary Supplement, September 19, 1918. Athenaeum, January, 1919.

- ↑ Athena nrs. 1 and 3, Lisbon, 1924.

- ↑ A Voz do Silêncio (The Voice of Silence) at the Portuguese National Library.

BESANT, Annie (1915), Os Ideaes da Theosophia, tr. Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora.

LEADBEATER, C. W. (1915), Compêndio de Theosophia, tr. Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora.

LEADBEATER, C. W. (1916) Auxiliares Invisíveis, tr. Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora.

LEADBEATER, C. W. (1916), A Clarividência, tr. Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora.

(1916), A Voz do Silêncio: e outros fragmentos selectos do Livro dos Preceitos Aureos, tr. ingleza e anot. por H. P. B., versão portuguesa de Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora.

(1916), Luz Sobre o Caminho e o Karma, transcriptos por M. C., com notas, commentarios, traducção de Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa: Clássica Editora. - ↑ nthposition online magazine: The magical world of Fernando Pessoa

- ↑ PASI, Marco (2002). "The Influence of Aleister Crowley on Fernando Pessoa's Esoteric Writings". The Magical Link 9 (5): 4–11.

- ↑ The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin classics, 2003.

- ↑ Letter to Adolfo Casais Monteiro, 13 January 1935.

- ↑ The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin classics, 2003, p. 474

- ↑ STEINER, George, «A man of many parts», The Observer, Sunday, 3 June 2001. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2001/jun/03/poetry.features1.

- ↑ PAZ, Octavio (1983), El Desconocido de Si Mismo: Fernando Pessoa in Los Signos en Rotacion y Otros Ensayos, Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- ↑ PESSOA, Fernando, Notas Para Recordação do Meu Mestre Caeiro in Presença nr. 30, Jan.-Feb. 1930, Coimbra.

- ↑ SHEETS, Jane M., Fernando Pessoa as Anti-Poet: Alberto Caeiro, in Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Vol. XLVI, Nr. 1, January 1969, pp. 39–47.

- ↑ Message, Tr. by Jonathan Griffin, Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2007.

- ↑ Mensagem 1st. edition, 1934, at the Portuguese National Library.

- ↑ MARTINS, Fernando Cabral (coord.) (2008). Dicionário de Fernando Pessoa e do Modernismo Português. Alfragide: Editorial Caminho.

- ↑ The Portuguese Republic was founded by the revolution of October 5, 1910, giving freedom of association and publishing.

- ↑ PESSOA, Fernando (1993). Textos de Crítica e de Intervenção. Lisboa: Edições Ática.

Further reading

Books

- Embodying Pessoa: corporeality, gender, sexuality / Klobucka, Anna. 2007

- Portuguese writers (Dictionary of Literary Biography) / Rector, Mónica. 2004

- Atlantic Poets: Fernando Pessoa's turn in Anglo-American Modernism Santos, Maria Irene Ramalho Sousa 2003

- Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds / Bloom, Harold. 2002

- Spanish and Portuguese literatures and their times: The Iberian peninsula / Moss, Joyce. 2002

- Stevens, Dana Shawn, A local habitation and a name heteronymy and nationalism in Fernando Pessoa, PhD Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. 2001

- Stevens, Dana Shawn, "A local habitation and a name heteronymy and nationalism in Fernando Pessoa", PhD Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. 2001

- Modernism's Gambit: Poetry Problems and Chess Stratagems in Fernando Pessoa and Jorge Luis Borges / Peña, Karen Patricia. 2000

- Fernando Pessoa and nineteenth-century Anglo-American literature Monteiro, George 2000

- Pessoa's Alberto Caeiro / (University of Massachusetts Dartmouth). 2000

- Dreams of dreams: and, The last three days of Fernando Pessoa / Tabucchi, Antonio. 1999

- The presence of Pessoa: English, American, and Southern African literary responses Monteiro, George 1998

- An Introduction to Fernando Pessoa: Modernism and the Paradoxes of Authorship Sadlier, Darlene 1998

- Modern art in Portugal: 1910-1940 : the artist contemporaries of Fernando Pessoa / Serra, Joao. 1998

- A Centenary Pessoa / Pessoa, Fernando. 1997

- Fernando Pessoa: photographic documentation and caption / Lancastre, Maria Jose de. 1997

- Fernando Pessoa: Voices of a Nomadic Soul / Kotowicz, Zbigniew. 1996

- The Western Canon / Bloom, Harold. 1994

- The Continuing Presence of Walt Whitman: the Life after the Life / Martin, Robert. 1992

- Fernando Pessoa: the Bilingual Portuguese Poet Terlinden-Villepin, Anne 1990

- Three Persons on One: A Centenary Tribute to Fernando Pessoa / McGuirk, Bernard. 1988

- Modern Spanish and Portuguese literatures / Marshall J Schneider. 1988

- Fernando Pessoa, a Galaxy of Poets / Carvalho, Maria Helena Rodrigues de. 1985

- Fernando Pessoa's The Mad Fiddler: A Critical Study / Terlinden-Villepin, Anne. 1984

- The Man Who Never Was: Essays on Fernando Pessoa / Monteiro, George. 1982

- Fernando Pessoa: the genesis of the heteronyms / Green, J. C. R. 1982

- Spatial Imagery of Enclosure in the Poetry of Fernando Pessoa / Guyer, Leland Robert. 1979

- The Role of the Other in the Poetry of Fernando Pessoa / Jones, Marilyn Scarantino. 1974

- Selected Poems of Fernando Pessoa / Rickard, Peter. 1972

- Studies in modern Portuguese literature / Faria, Almeida. 1971

- Three Twentieth-Century Portuguese Poets / Parker M., John. 1960

Articles

- Riccardi, Mattia, "Dionysus or Apollo? The heteronym Antonio Mora as moment of Nietzsche's reception by Pessoa" in Portuguese Studies 23 (1), 109, 2007.

- Suarez, Jose, "Fernando Pessoa's acknowledged involvement with the occult" in Hispania 90 (2): 245-252, May 2007.

- De Castro, Mariana, "Oscar Wilde, Fernando Pessoa, and the art of lying" in Portuguese Studies 22 (2): 219-+ 2006

- Beyer, Bethany, "Borges and Pessoa: Authorial voices and esoteric reflections", M.A. Dissertation, Brigham Young University., 2006

- Ribeiro, A. S., "A tradition of empire: Fernando Pessoa and Germany" in Portuguese Studies 21: 201-209 2005

- Hale, Michelle, "Ironic multiplicity: Fernando's "pessoas" suspended in Kierkegaardian irony", M. A. Dissertation, Brigham Young University., 2004

- McNeill, Pods, "The aesthetic of fragmentation and the use of personae in the poetry of Fernando Pessoa and W.B. Yeats" in Portuguese Studies 19: 110-121 2003

- Muldoon P., "In the hall of mirrors: 'Autopsychography' by Fernando Pessoa" in New England Review 23 (4), Fal 2002, pp. 38–52

- Bloom, Harold, "Fernando Pessoa", in Genius: a mosaic of one hundred exemplary creative minds: Pub. New York: Warner Books., 2002

- Steiner, George, "A man of many parts" in The Observer, Sunday, 3 June 2001.

- Wallace, James, "Camões, Pessoa, Bloom and the poetry of heteronomy as solution for the anxiety of influence", M.A. Dissertation, Brigham Young University, 2000.

- Bamforth, I., "An Introduction to Fernando Pessoa: Modernism and the paradoxes of authorship" in Parnassus 24 (1), 1999, pp. 286–303.

- Bamforth, I., "The presence of Pessoa: English, American and Southern African literary responses" Parnassus 24 (1), 1999, pp. 286–303.

- Hicks, J., "The Fascist imaginary in Pessoa and Pirandello" in Centennial Review 42 (2): 309-332 SPR 1998

- Mahr, G., "Pessoa, life narrative, and the dissociative process" in Biography 21 (1) Winter 1998, pp. 25–35.

- Haberly, David T., "Fernando Pessoa: Overview" in Reference Guide to World Literature, second ed., edited by Lesley Henderson, St. James Press, 1995.

- Lopes J. M., "Cubism and intersectionism in Fernando Pessoa's 'Chuva Obliqua" in Texte(15-16),1994, pp. 63–95.

- Zenith, Richard, "Pessoa, Fernando and the Theater of his Self" in Performing Arts Journal(44), May 1993, pp. 47–49.

- Anderson, R. N., "The Static Drama of Pessoa, Fernando" in Hispanofila (104): 89-97 JAN 1992

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Was Pessoa Ever in South Africa?" in Hispania, Volume 74, Number 3, September 1991.

- Brown, S.M. , "The Whitman Pessoa Connection" in Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 9 (1): 1-14 SUM 1991.

- Eberstadt, Fernanda, "Proud of His Obscurity", in The New York Times Book Review, Vol 96, September 1, 1991, p. 26.

- Dyer, Geoff, "Heteronyms" in The New Statesman, Vol. 4, December 6, 1991, p. 46.

- Monteiro, George, "The Song of the Reaper-Pessoa and Wordsworth" in Portuguese Studies 5, 1989, pp. 71–80.

- Cruz, Anne J., "Masked Rhetoric: Contextuality in Fernando Pessoa's Poems", in Romance Notes, Vol. XXIX, No. 1, Fall, 1988, pp. 55–60.

- Hollander, John, "Quadrophenia", in New Republic, September 7, 1987, pp. 33–6.

- Rosenthal, David H., "Unpredictable Passions", in The New York Times Book Review, December 13, 1987, p. 32.

- Guyer, Leland, "Fernando Pessoa and the Cubist Perspective", in Hispania, Vol. 70, No. 1, March 1987, pp. 73–78.

- Bunyan, D, "The South-African Pessoa: Fernando 20th Century Portuguese Poet", in English in Africa 14 (1), May 1987, pp. 67–105.

- Seabra, J.A., "Pessoa, Fernando Portuguese Modernist Poet", in Europe 62 (660): 41-53 1984

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Pessoa, Fernando - A Modern Lusiad", in Hispania 67 (1): 52-60 1984

- Howes, R. W., "Pessoa, Fernando, Poet, Publisher, and Translator", in British Library Journal 9 (2): 161-170 1983

- Sousa, Ronald W., "The Structure of Pessoa's Mensagem", in Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Vol. LIX, No. 1, January 1982, pp. 58–66.

- Severino, Alexandrino E., "Fernando Pessoa's Legacy: The Presença and After", in World Literature Today, Vol. 53, No. 1, Winter, 1979, pp. 5–9.

- Wood, Michael, "Mod and Great" in The New York Review of Books, Vol. XIX, No. 4, September 21, 1972, pp. 19–22.

- Sheets, Jane M., "Fernando Pessoa as Anti-Poet: Alberto Caeiro", in Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Vol. XLVI, No. 1, January 1969, pp. 39–47.

External links

- Fernando Pessoa's Biography at Shearsman Books

- Fernando Pessoa at Vidas Lusófonas

- Fernando Pessoa at Enotes

- Fernando Pessoa at Astrotheme

- Pessoa's Trunk by Marc Weidenbaum

- Fernando Pessoa Museum (Casa Fernando Pessoa)

- Multipessoa

- Arquivo Pessoa

- Poets.org Biography

- The Lonely Crowd

- Excerpts from The Book of Disquiet, in English

- Poem of Pessoa on a fort just off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- John Gray: Assault on Authorship

- John Hollander: Quadrophenia

- Dror Poleg: 'Incredulity towards Postmodernism: Baudrillard, Pessoa, and the Simulacra of Precession'

- Luis Filipe Teixeira: Pessoa essays in Portuguese

- Nos Jardins do Ofício: Pessoa e a Alquimia do Verbo

- Narciso e o Espelho. Virtualidade e Heteronímia ou as viagens pessoanas de Alice

- Corporeidades heteronímicas do Eu: Breve reflexão em torno da Estética pessoana

- A Casa e o Mundo

- Camões/Pessoa: Poetas da Viagem Utópica

- Kirjasto Biography

- Pessoa revisited (intertextuality)

- Poems of Fernando Pessoa

- Poems of Fernando Pessoa read in English and Portuguese

- Instituto de Estudos sobre o Modernismo / FCSH - UNL

- Portuguese National Library